Ed. Note: This post is co-authored by Bob Lewis, Senior Principle Consultant, Digital Business Consulting, Dell Digital Business Services

Until recently, the importance of velocity in IT’s processes and practices has been largely ignored. Even before the recent emphasis on the strategic value of digital technologies, the acceleration of business and IT’s integral role in it were both well-accepted ideas, and yet IT’s failure to keep pace mostly went unrecognized.

Not only has the importance of IT velocity been ignored, much of what’s traditionally been considered best practice for information technology deliberately sacrifices speed and functionality for risk management and cost containment.

This is, at last, changing. In large part due to the ever-increasing need for speed driven by digital businesses. Gartner, for example, is actively promoting a bimodal model, in which traditional IT practices remain in control of a company’s systems of record, while speedier and more agile alternatives hold sway for “systems of engagement.”Systems, which directly or indirectly connect to a company’s customers and consumers.

But many current industry recommendations miss two key issues that matter when the subject is IT organizational velocity and agility.

The first is that “system of record” and “system of engagement” aren’t mutually exclusive classifications. Being “of record” and being used for engagement are independent attributes. A system of record might or might not also be a system of engagement and vice versa.

Take the company’s CRM system. It clearly is a system of record, as it contains the primary data for every customer. And, as the CRM system is used to schedule and manage many customer touchpoints, it’s just as clearly a system of engagement.

The second and more important issue is that “system of record” and “system of engagement” are application properties.

But application characteristics aren’t what drive tradeoffs among speed, quality, feature-richness, cost, and so on. They’re consequences, not of applications, but of the different timescales in which a company operates. Different types of business change drives the need for different speeds and adaptation priorities, which don’t respect the largely illusory boundary separating systems of record from systems of engagement.

Speed modes

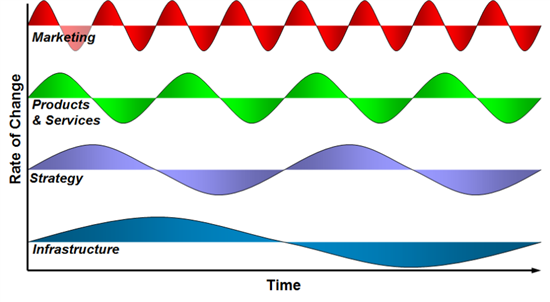

Consider Figure 1. As it illustrates, businesses typically operate at four very different rates of change:

Figure 1 – Business Speed Modes

Infrastructure – slow and profound

The history of IT in the enterprise began in business infrastructure time, with the use of computers to support core accounting functions.

At its heart, accounting hasn’t changed all that much since Paccioli invented it five hundred years ago: Debits are still on the left; credits are still on the right.

Certainly, the field hasn’t been static since then, but it’s still fair to say that of all corporate functions, accounting is the most stable … intentionally so.

Infrastructure is, by definition, what the rest of a business is built on. And whether it’s accounting, human resources, or the communications environment, the systems supporting corporate infrastructure take time and care to implement, (as anyone who has been involved in an ERP implementation can testify).

Also, changes to infrastructure and its supporting systems have broad impact and ripple effects, making infrastructure much more disruptive to alter than practices and supporting systems at any other level.

Infrastructure has another, rarely recognized impact: Because infrastructure changes are slow, difficult and expensive, infrastructure facilitates some possible corporate strategies and tactics while hindering or preventing achievement of other goals and tactics a business otherwise might logically pursue. Infrastructure shapes strategy far more than strategy dictates infrastructure. Which, in turn, means companies must make infrastructure decisions carefully. Typically they’ll last a decade or more, placing profound constraints on unpredictable future circumstances throughout their lifetime.

Strategy – plans for the foreseeable future

Strategy is about long-range planning, “long range” meaning as far into the future as it’s possible to look with any reasonable hope of accuracy.

In most industries, this might mean three years, and as business cycles continue to compress, the lifespan of future business strategies will be even shorter.

And yet, to turn strategy into operational reality requires new or changed business practices and processes that will depend on new or changed information technology to maximize their effectiveness. Companies can’t turn strategy into action without a roadmap, but once they have one, success requires disciplined project management and insightful organizational change management.

To cope with business-cycle compression, businesses are increasingly turning to Agile management techniques. But while Agile is considered proven practice for small-scale software development and business change, strategy implementation is by definition large in scope, calling for “scaled Agile,” a discipline still in, if not its infancy, no more than early adolescence.

Product – the new-and-improved timescale

It’s rare that mature businesses can base their strategy on a single product or service; certainly they can’t base it on a single generation of a single product or service.

Business strategies generate product plans; as these exist within the span of business strategy they are, quite clearly, shorter. Which, in turn, means the systems critical for product management—everything from Product Information Management (PIM) systems in retail, to supply chain and manufacturing management systems—have to change and adapt in product time. To support product planning and execution, IT has to deliver software change in spans measured in months, not years.

Marketing time – the pace-setter for high-speed IT

Compare infrastructure to the other end of the scale—Marketing Time.

In the early days of the World Wide Web, Marketing Time was why the web experienced such explosive growth. Had the web been subjected to IT’s safety-ridden disciplines, content and functionality would have trickled onto the web at a small fraction of its actual pace of growth and development. But because marketing was in control of the process, companies threw material and functionality onto the web, and played with it … there’s no other word for the process … until it was what it needed to be.

In the early days of the Web, Marketing Time operated in terms of campaigns—a lifecycle of a few months at most—as one product might be advertised and sold through more than one campaign. This was a systems lifespan few IT organizations knew how to cope with. Many still don’t.

And we’re rapidly entering an age when distinct marketing campaigns are considered a quaint relic of a slower time. We are entering the age of microtemporal message cycles.

Or perhaps we’ve already entered it. Time in microtemporal message cycles is measured in tweets per hour or day, and IT will have to provide systems that trigger humans to write, proof, vet, and send them in response to events.

Or, as business IT becomes more comfortable with these technologies, to automatically generate marketplace messages using artificial-intelligence-based event-detection and authoring engines. The integration challenges associated with a true automated microtemporal messaging system are daunting, but from a staffing and branding perspective the alternatives are even more so.

IT’s operating modes

As described above, we believe businesses operate at more than two speeds, which means IT has to operate at more than two speeds as well.

It also strongly suggests the distinction between systems of record and systems of engagement is questionable, and at best only part of the discussion: Most systems that engage with customers make promises to them of one kind or another. A system that makes a promise to a customer is a system of record in any business that considers keeping its promises to its customers important.

But the justification for and nature of multimode IT goes beyond just velocity and reliability. It extends to the operating models, business goals, and corporate culture of the different constituencies with which IT collaborates.

Future posts will deal with these and other drivers and consequences of the need for multimode IT and how companies should be addressing these needs.

To learn more about High Speed Digital IT, please see out new mobile responsive Digital Business Services pages on dell.com

About the co-author:

Bob Lewis is a senior management consultant with Dell Digital Business Services and has published 12 books and more than 1500 articles on IT transformation. He is a trusted C-level advisor for IT strategy, enterprise architecture and business culture. He is frequently called upon to lead transformation workshops.