Imagine you’re the CFO of a prominent organization. Two days ago, you hosted a dinner event with the company’s executive team—and posted photos of the evening on social media.

When you receive a friendly follow-up message from the CEO thanking you for the evening and mentioning other attendees by name, you think nothing of it. By the way, she asks—could you wire some funds to that new client? You know, the one you two were chatting about at the party? You don’t remember the conversation, but you make the transfer without a second thought.

An ocean away, the scammer impersonating the CEO cashes out your company funds.

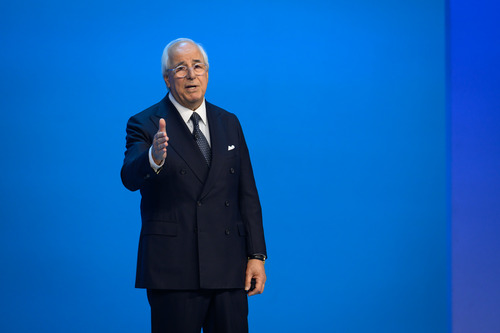

Frank Abagnale Jr., a renowned international cybersecurity and fraud prevention consultant, painted this picture at a recent panel during the Dell Technologies World 2023 conference. He added that it’s unlikely the company in this hypothetical situation will ever see those stolen dollars again. “They may catch and convict the person responsible, but it’s unlikely you’ll ever recover your money,” he said. In fact, at the end of 2022, there was more than $110 billion in court-ordered restitution outstanding across federal, state, county, and municipal entities. Ninety-one percent of that money will never be collected.

Abagnale’s cautionary tale demonstrates just one type of threat that modern enterprises face. It also underscores that while technology continues to evolve, considering the “human factor”—as both a potential weakness and critical defense—is non-negotiable.

“What I did 50 years ago is 4,000 times easier to do today. With AI, it’ll be 5,000 times easier in the next few years.” – Frank Abagnale, Jr., cybersecurity and fraud prevention consultant

Cultivating a secure innovation culture from the top-down

Abagnale’s anecdote illustrates the increasing sophistication of social engineering, with criminals leveraging social media and artificial intelligence (AI) to mount more convincingly deceptive attacks. Given the growing threat of generative AI, every organization, regardless of its size, needs to adopt a mindset of hyper-vigilance to defend sensitive data—including implementing both financial safeguards and intellectual property (IP) protections.

Often, it’s up to an organization’s technology leadership to instill a security-first culture from the top down—especially as more and more studies suggest that data breaches typically result from human error. Abagnale backs this up: “Hackers don’t cause breaches. People do,” he said. “People leave doors open and create opportunities.” Bobbie Stempfley, facilitator of the panel discussion, summarized this sentiment: “Technology is core to security strategies, but that’s an incomplete picture. What’s really common across all of this is the humans and the human impact on digital risk.” She went on to note that while a “culture of security” can be advantageous to organizations, one of the biggest hurdles to implementing such policies boils down to getting buy-in across all departments. “Adopting any kind of new strategy requires humans to change, and that can be difficult—particularly when we talk about the broad, systemic changes that are simply looking for those opportunities necessary to address digital risk.”

As such, leadership must take steps to seal any gaps preemptively—often by working in tandem with IT and data security teams to enact effective defense systems that are fit for modern realities. However, a surprising statistic from the Dell Technologies Innovation Index reveals that 45% of business decision-makers still don’t regard their IT team as an important business partner.

This disconnect is downright dangerous. “If you believe you have a foolproof system, you’re failing to take into consideration the creative fools,” said Abagnale, whose extraordinary life inspired the film Catch Me If You Can about a teenager who forged $2.5 million in fraudulent checks across 26 countries. “What I did 50 years ago is 4,000 times easier to do today. With AI, it’ll be 5,000 times easier in the next few years.”

Designing security processes around human behavior

Trust, noted panel participant Oz Alashe, founder and CEO of behavioral risk assessment firm CybSafe, is the bedrock of a functioning society. “It’s built into every single thing that we do. It’s a fundamental, necessary glue that binds us together,” he said.

It is perhaps paradoxical then, pointed out Stempfley, facilitator of the panel discussion, that in a world in which trust is so foundational, architectures like Zero Trust are becoming ever more popular—and necessary. “How do we move to a more Zero Trust-driven world, which is about not trusting anything, and create the right balance of just enough friction to make things more obvious, identifiable, and protected—but not so much that people won’t use the capability?” she asked.

First and foremost, noted Alashe, the people building user experiences—and information security architectures like Zero Trust—need to take human behavior into consideration from the ground up. “Those of us who build technology need to really double down on human-centered design—designing digital products and services with a human focus on needs, privacy, and security,” he said.

Alashe also emphasized the importance of continuously reevaluating security protocols to keep pace with evolving innovation ecosystems. For example, technological advancements like blockchain, with its decentralized and immutable nature, have the potential to revolutionize corporate transparency and accountability. Digital identity authentication and biometric authentication technologies, too, can help establish trust.

But however such safeguards are designed and implemented, Alashe cautioned it’s critical that the onus of cybersecurity doesn’t fall to the individual user. “It’s key that we’re not placing the burden on the user. Sometimes as technologists, we actually make it slightly more complicated than we need to… if we want to influence people’s behavior, we need to make it easy,” he said.

Investing in ongoing education and user support

Abagnale noted that knowledge is one of the most powerful tools in the arsenal against cybercrime including social engineering schemes. “If I can show you how the scam works and you understand it, you will not fall victim to that scam,” he said.

Alashe echoed this idea, but elaborated that mere awareness of cyber threats is no longer sufficient—the underpinning support technology must also be robust. “We need to promote digital literacy and empower individuals to be not only just aware of risks, but also confident and [capable of] thinking critically,” he said.

This is becoming more realistic nowadays, as technology advancements, a better understanding of change-management theory among business leaders, and Zero Trust architectures make it easier to predict and defend against risky behaviors before they manifest. “We will never fully eradicate risk. But there will come a time when virtually every single device considers the people using them and gives them the help and support that they need,” said Alashe. “It’s a better, more scientific, and more data-driven way to be. Our people deserve better. We need to give them better. That way we will earn that trust.”

Stempfley seconded Alashe’s concluding remarks. “I think [security professionals are] going to start talking a lot more about how we take education and turn it into behavioral change—and how we really think about how to employ technology to improve the situation,” she said. “As we all know, innovation happens, and we need to have the right kind of security principles early in the process.”

![]()